14/04/2025

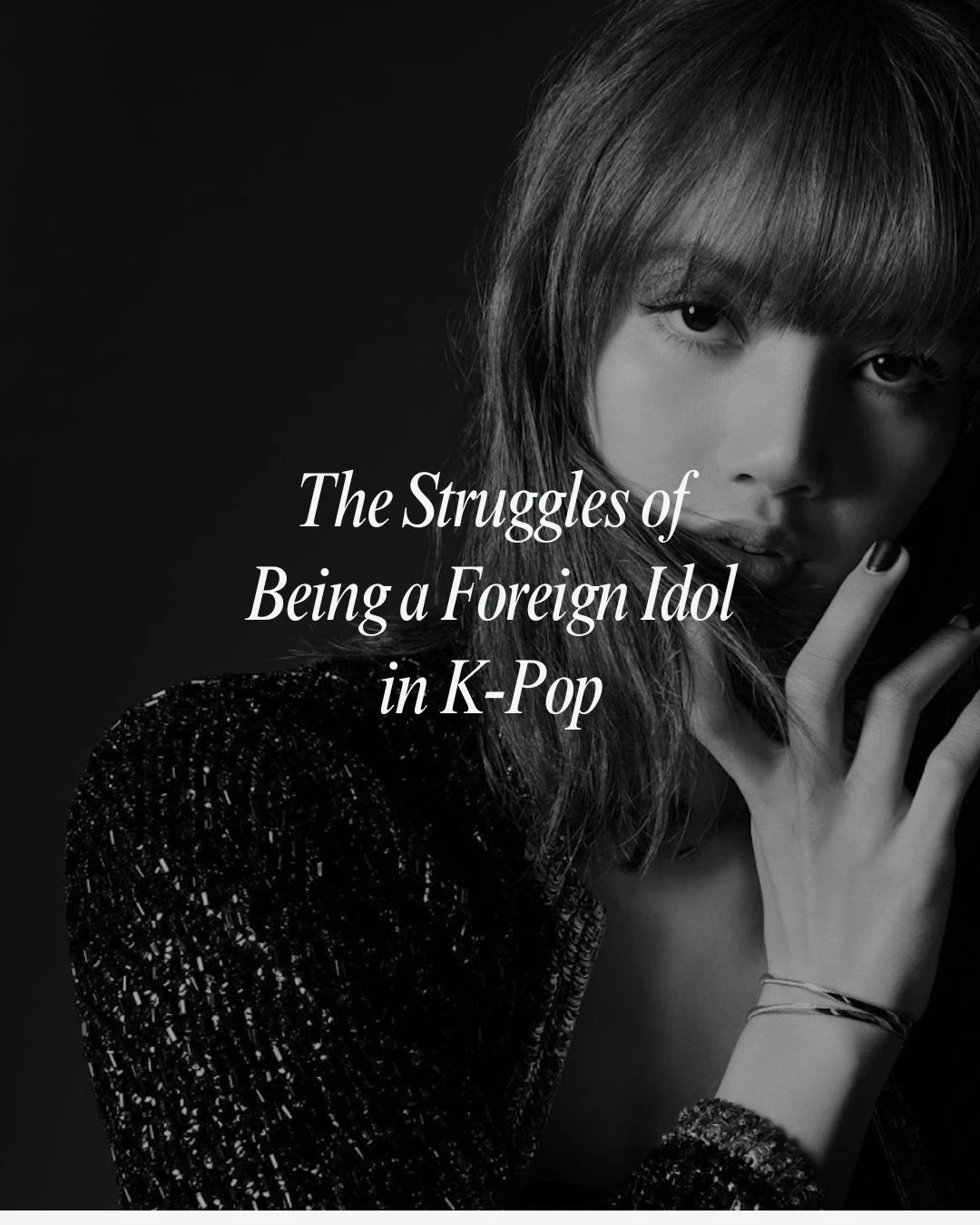

The Struggles of Being a Foreign Idol in K-Pop

Trying to make it in K-pop is no easy feat, and for foreign idols, the road is even rougher. Many have shared how difficult it is to earn the same respect as Korean idols and be seen as equals in the fiercely competitive Korean entertainment industry.

Table of Contents

- Foreign Idols in a Korean-Dominated Scene

- Korean Society: A Foundation of Homogeneity

- Visual Perfection: Non-Debatable in the Industry

- The Appeal and Limitations of Foreign Members

- Harsh Contracts and the Business of Profit

- Language & Culture: The Heavy Burden on Foreign Trainees

- Lack of Support and Discrimination in Practice

- Sorn and Elkie: Pay Gaps and Marginalization

- aespa’s Giselle and NingNing: The Subtle Exclusion

- BLACKPINK’s Lisa: Enduring Unfair Treatment

- An Overall Lack of Progress: A Frustrating Reality

- Conclusion: A Call to Expand the Industry’s Vision

Foreign Idols in a Korean-Dominated Scene

Despite K-pop’s global reach—where fans from every corner of the world admire Korean idols—the industry remains heavily Korean-centric, with the occasional East Asian exceptions. Most so-called “foreign” idols tend to be of Asian descent or are half-Korean, such as Ju Haknyeon of THE BOYZ or Huening Kai of TXT, while idols like BLACKSWAN’s Gabi and Fatou, who are non-Asian, remain rare. Many wonder why, to this day, the Korean idol scene is so racially exclusive when it’s clear that non-Koreans can succeed if given proper support.

The short answer is that while adding foreign members can be beneficial—tapping into new fanbases—most companies appear hesitant to do so, preferring safer, more traditional lineups that conform to domestic audiences’ tastes. This leaves countless talented individuals from around the world struggling to even get their foot in the door.

Korean Society: A Foundation of Homogeneity

One undeniable factor is South Korea’s demographic structure. As of 2019, foreigners made up only about 4.9% of the country’s population. With the entertainment industry primarily aimed at domestic viewers, companies naturally try to cater to their largest market: ethnic Koreans. This is reflected in the K-pop idol groups they create, who embody cultural norms and aesthetics popular with local audiences.

In a largely homogeneous society, fitting in can matter immensely. Trainees who are perceived as outsiders face an uphill battle to gain acceptance, both by local fans and the mainstream media. This “Korean-first” mindset makes it harder for foreigners—particularly those without East Asian features—to be embraced as part of the K-pop family.

Visual Perfection: Non-Debatable in the Industry

K-pop is known for its strict visual and performance standards. Many idols undergo plastic surgery, rigid diets, and punishing training to achieve an ideal image. Companies worry that non-Asian features might not align with these conventional norms, potentially making a foreign trainee stand out in a negative way instead of blending seamlessly with the group’s aesthetic.

This fear of deviation from established beauty standards makes agencies hesitant to invest heavily in a foreign idol. While the end goal of K-pop is to create uniform, visually appealing groups, ironically, fresh and diverse appearances could appeal to global fans—yet the domestic audience’s preferences often hold more weight. Companies are thus reluctant to gamble on someone who might fail to conform to what Korean fans expect in terms of “perfection.”

The Appeal and Limitations of Foreign Members

Not everything is doom and gloom, though. Having a foreign member can open doors to new markets by drawing in fans from that idol’s country of origin. It’s a strategic tool often used for neighboring markets like Japan or China. For instance, certain groups rely on Japanese or Chinese members to strengthen their foothold abroad. However, rarely do we see the same approach used with completely non-Asian members, largely because agencies remain uncertain about the potential domestic backlash.

Moreover, a foreign trainee might land a spot under a lesser-known agency eager for publicity. While this can generate buzz, it also risks fleeting popularity; without consistent investment or follow-up promotions, these idols may quickly fade. For the K-pop industry, it’s all about balancing the perks of appealing to foreign markets against the potential challenge of satisfying Korean fans who might be less accepting of “outsiders.”

Harsh Contracts and the Business of Profit

At its core, K-pop is still a profit-driven business. Training and debuting an idol requires a substantial financial investment. If these idols fail to deliver sufficient returns, companies are quick to terminate contracts or, in some cases, saddle them with debt. For foreign idols, this dynamic is even more precarious. If they lose their position, they risk uprooting their entire life in Korea, with few safety nets or supportive networks to help them recover.

The K-pop trainee system often includes “debt clauses,” forcing idols to repay all training costs if they fail to “make it.” When you’re a foreigner, that risk multiplies—because moving back home can mean giving up not just a career but also the social and cultural ties you’ve built. In many cases, trainees discover that their dream of stardom was overshadowed by exploitative terms that left them with staggering debts and insufficient pay.

Language & Culture: The Heavy Burden on Foreign Trainees

Becoming a K-pop idol is about more than just singing and dancing. Language fluency is critical. Foreign trainees usually have limited knowledge of Korean at the start, forcing them to juggle intense daily training with language classes and cultural assimilation. Few agencies provide extensive support for these needs, especially among smaller labels. As a result, many foreign idols navigate language barriers on their own, fueling added stress and isolation.

For some companies, foreign idols represent an intriguing opportunity, so they may be somewhat lenient, giving these idols more time to study the language or adjust. But it’s inconsistent at best, often hinging on the idol’s potential to become the group’s “marketable foreign face.” The pressure to adapt swiftly can be overwhelming, leading some idols to burn out or feel they’ll never genuinely belong.

Lack of Support and Discrimination in Practice

Even if a foreign idol manages to debut, the ordeal isn’t over. Many have complained about a lack of adequate agency support—ranging from fewer promotional opportunities to minimal resources for coping with cultural differences. Fans have long criticized these companies for advocating “global groups” while failing to truly nurture or promote their non-Korean members. The reality is often that foreign idols get shoved aside if their star power doesn’t immediately skyrocket.

The problem isn’t just about public acceptance; it extends to within the industry. Some idols recall feeling singled out or facing microaggressions from staff who question whether they “belong.” Others mention how they’re forced to adapt more than their Korean counterparts, facing stiffer punishments or scolding for mistakes—just because they’re “outsiders” who should “know better” or be extra grateful for the chance to be in K-pop at all.

Sorn and Elkie: Pay Gaps and Marginalization

Former CLC members Sorn (Thai) and Elkie (Hong Kong) have publicly shared their financial struggles, noting a pay gap between them and their Korean peers. Sorn mentioned how non-Korean trainees can end up with less favorable contracts, earning far lower salaries despite undergoing the same rigorous training. Elkie confirmed that this disparity trickles into promotional opportunities, endorsements, and overall financial security.

This scenario underscores a bigger truth: foreign idols often find themselves undervalued, with companies investing less in them because of concerns they might not attract Korean fans or align with local beauty standards. It’s unfair to watch such talent be minimized simply because they weren’t born Korean—and, from fans’ perspective, it’s a grossly missed opportunity to capitalize on diversity.

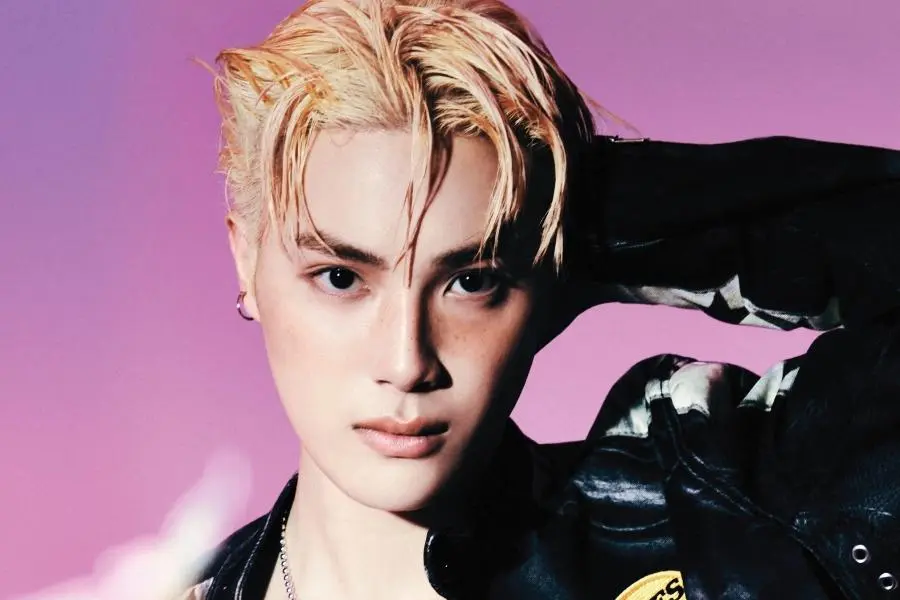

aespa’s Giselle and NingNing: The Subtle Exclusion

Even idols from major companies like SM Entertainment aren’t exempt from unfair treatment. In aespa, Giselle (half Korean, half Japanese) has become a frequent target of hateful remarks, with some questioning her authenticity simply because she isn’t fully Korean. Fans point to promotional activities where Giselle was left out or overlooked, such as “Club Clio Japan” campaigns or MLB Korea’s promotional material spelling her name incorrectly. Similarly, her groupmate NingNing (Chinese) has faced repeated instances of being excluded from schedules or promotional posts, fueling fan outrage.

These subtle (and sometimes glaring) omissions confirm that even well-known companies do a lackluster job of supporting their foreign members. No matter how talented or beloved by international fans, they risk being seen as second-class idols within their own group’s promotional ecosystem.

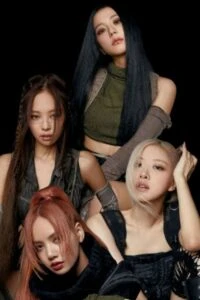

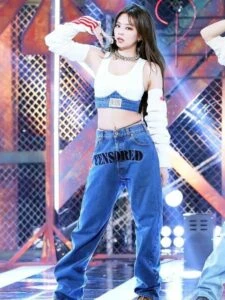

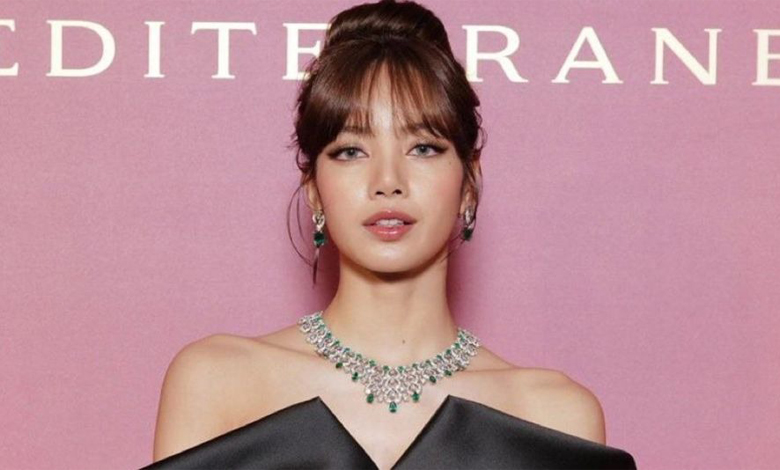

BLACKPINK’s Lisa: Enduring Unfair Treatment

Arguably one of the most famous foreign idols is BLACKPINK’s Lisa from Thailand. Despite her massive popularity, she frequently faces racial or cultural discrimination. Some fans allege that Lisa’s promotional opportunities are fewer compared to her bandmates and point to hashtags like #RespectLisa or #YGLetLisaWork, demanding better treatment for her. The situation echoes statements made by Sorn and Elkie about unequal pay and coverage for non-Korean members, illustrating that even superstars in top-tier groups aren’t immune to prejudice.

Though Lisa is an indisputable global sensation, netizens continue to single her out with derogatory remarks about her Thai heritage or her “foreign” look. Observers note the double standard: her groupmates may be lauded for their beauty or style, while Lisa endures critiques for the very aspects that make her stand out. The lack of official pushback from agencies only worsens the situation, normalizing the biased treatment.

An Overall Lack of Progress: A Frustrating Reality

Year after year, fans raise concerns on social media and forums about how foreign idols are mistreated, underpromoted, or given unfair contracts. Yet the industry’s focus on profit and conventional norms slows any real, systemic change. While K-pop aims to brand itself as global, the reality for many “foreign” idols is an environment lacking robust support, fair pay, or acceptance from local fans.

It’s hard not to see the disconnect: agencies talk about their “global aspirations,” yet shy away from giving foreign idols the necessary resources. Critics point to a cyclical failure: companies sign foreigners to generate hype but fail to invest in them long-term or defend them from public bias. This, in turn, keeps the foreign idol from achieving success comparable to their Korean members, reinforcing the idea that foreign idols don’t “work” in K-pop.

Conclusion: A Call to Expand the Industry’s Vision

The question remains: Can the K-pop industry truly become global if it fails to protect and promote its foreign idols on an equal footing? For all the hype about cultural exchange and global fandoms, it appears the industry itself still operates within a narrow framework. Corporate decisions are guided by conservative attitudes—fearing that an “unfamiliar” face might alienate local fans, or that a foreign member might not measure up to Korean beauty standards.

If K-pop truly wants to embrace its international audience, it needs to offer fairer contracts, genuine support, and a more inclusive approach for non-Korean idols. This shouldn’t be a matter of meeting quotas or tokenism—rather, it’s about giving deserving talent a level playing field, regardless of their ethnicity or background.

The future of K-pop could be brighter and more diverse if these deep-seated issues are addressed. As more fans worldwide demand representation and justice for foreign idols, the industry might be compelled to evolve. Until then, countless gifted individuals will keep hitting the same walls, struggling to prove they belong—and for some, the dream of making it in K-pop might remain just that: a dream unfulfilled.